Performance-related play?

The Triple Bottom line helped wrestle sustainability away from finger-wagging morality, but that still doesn't mean we're buying it.

It’s Spring Statement time in the UK and things are not looking good. The annual search under the nation’s fiscal sofa cushions has failed to fill a £15bn spending gap and the result is big cuts to services and welfare spending.

Across the Atlantic, something similar is underway — although, with chainsaws — where Elon Musk’s DOGE is carrying out a wave of cuts to public spending that has had heads spinning.

I’ll let others thrash out the morality and economics and focus (unsurprisingly) on some of the communications and what it means for climate, nature, sustainability and circular economy communications.

Cuts & Cash: How the language of efficiency can hold us back

It’s 30+ years since John Elkington coined the term the Triple Bottom Line of People, Planet and Profit (also known as the 3Ps, TBL or 3BL). It was a major leap forward in how we make a case for sustainability and its various spin offs.

At times like these, when the headlines are dominated by things like inflation, employment, and spending, and when the purse strings constrict tighter than a hungry anaconda, TBL can feel like a life ring for sustainability professionals. It gives us something to cling to in seriously choppy financial seas, helping us maintain a business case for ‘doing the right thing.’

But Elkington himself has called for a rethink on TBL, noting:

It was supposed to provoke deeper thinking about capitalism and its future, but many early adopters understood the concept as a balancing act, adopting a trade-off mentality.

In 2019, marking the framework’s 25th anniversary, he proposed a recall of TBL (you can read it here), highlighting how it had been co-opted as an accounting tool at the expense of its higher ambition of systems change.

It was originally intended as a genetic code, a triple helix of change for tomorrow’s capitalism, with a focus was on breakthrough change, disruption, asymmetric growth (with unsustainable sectors actively sidelined), and the scaling of next-generation market solutions.

To be fair, some companies did move in this direction, among them Denmark’s Novo Nordisk (which rechartered itself around the TBL in 2004), Anglo-Dutch Unilever, and Germany’s Covestro. The latter company’s recently retired CEO, Patrick Thomas, has stressed that the proper use of the TBL involves, at minimum, progress on two dimensions while the third remains unaffected. It is time for this interpretation to become the default setting not just for a handful of leading businesses, but for all business leaders.

Not an accounting framework and not a communications one either

Elkington never intended for TBL to become an accounting framework, and it’s clear it was never intended as a communications and marketing one either. But that has not stopped us from trying to use it that way.

TBL quickly filtered into the way we started to talk about climate and nature solutions in almost every conversation — whether we are talking about buying a cup of coffee, a new car, or investing in a fund. We have turned TBL into buzzword bingo:

Good for people? ✔

Good for the planet? ✔

Good for your pocket? ✔

The problem is that the big lifestyle decisions that the climate conversation needs us to have (from what we eat, where we live, who we work for and how we raise our families) are only partially about these kind of rationale performance metrics. The other part is a much more complex web of factors.

Take the adoption of cars over horses a century ago.

For millennia, horses were central to human life – for transport, work, and status. They were the cultural embodiment of values such as loyalty, hard work, and courage (just think of the number of statues and paintings of military leaders perched on their equine equivalents).

Then came the automobile, a clunky, expensive, and unreliable piece of technology.

Yet, within a few decades, it surpassed the pony fundamentally reshaped our world.

This wasn't just about a superior technology replacing an older one. While concerns about city sanitation and the limitations of equine travel played a role, the car’s success was deeply rooted in something more profound: it captured our imagination and tapped into fundamental human desires. It wasn't just a faster way to get around; it became a symbol of freedom, independence, and the promise of a new, exciting future. Henry Ford was wrong, people didn't just want a better horse; they wanted something that aligned with their aspirations.

This historical shift offers a powerful lesson as we grapple with the climate crisis — especially as we do so in the middle of huge economic turmoil. It’s a reminder that while the need for a business case is there, don’t expect that to be the thing that connects with a community of any size or shape — your colleagues, your city, your family — and brings them with you.

Just as the early automobile industry didn't solely focus on the drawbacks of horses, but rather on the allure of the car, our approach to communicating about the value of climate and nature solutions needs to remember the things that sit outside metrics like TBL.

Even in times of economic pressure, or perhaps even more so in those times, this involves connecting climate-friendly choices to people's values, identities, and aspirations.

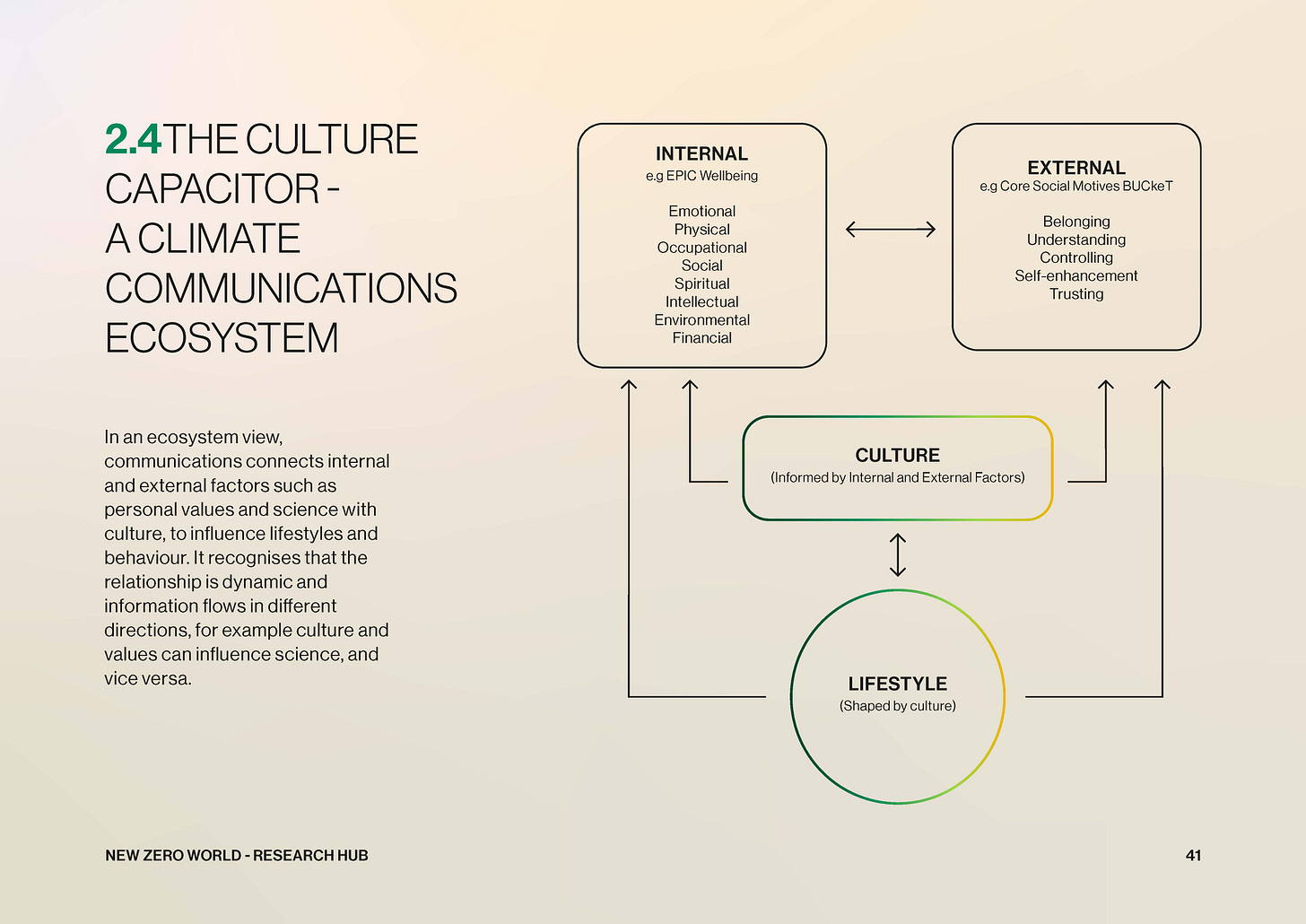

It’s something we set about trying to visualise for the recent Pop Culture: Bursting the Climate Communications Bubble report, for which I was lead author. We came up with something that hopefully helps better represent the factors involved in these big decisions, and importantly how we can connect to them.

Ultimately, the story of cars replacing horses wasn't just a technological transition; it was a cultural revolution driven by a compelling vision. To truly address the climate crisis, we need to similarly ignite the collective imagination by recognising the cultural complexity that underpins any big shift in behaviour.

Further reading

Pop Culture: Bursting the Climate Communications Bubble | New Zero World